Finding new international suppliers and reconfiguring supply chains takes time and money. As Grossman et al. (2024) and Baldwin and Freeman (2022) emphasise, finding new suppliers abroad involves substantial search and matching costs, including identifying reliable partners, ensuring compliance with local rules and regulations, and establishing new logistics networks. Due to these costs, relationships along the supply chain tend to be sticky, with even large importers often relying heavily on foreign suppliers from a single country (Antràs et al. 2017). Multinationals such as Apple may have a geographically diversified supplier base, but they are not representative.

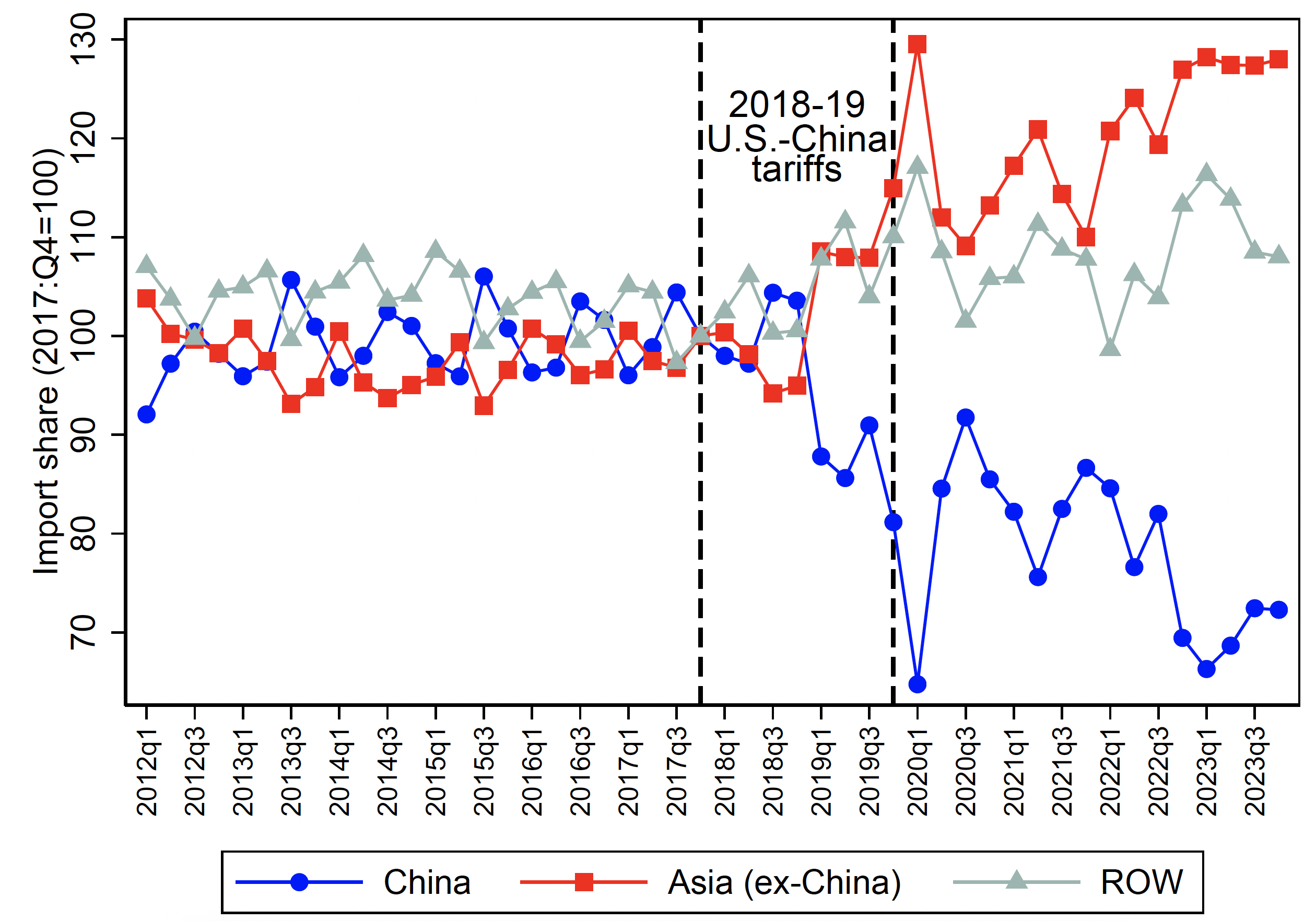

In recent years, global supply chains have come under intense pressure. Rising tariffs, geopolitical risks, and the COVID-19 pandemic have upended the flow of goods around the world (Aiyar et al. 2024). Having once relied heavily on Chinese suppliers, US importers have started to rethink their sourcing strategies – a shift that economists have dubbed the ‘Great Reallocation’ of trade (Antràs 2020, Alfaro and Chor 2023, Goldberg and Reed 2023, Fajgelbaum et al. 2024). Figure 1 depicts the shift in maritime trade shares for US firms, showing that their import share from China fell by close to 30% between 2017 and 2023.

Figure 1 The ‘Great Reallocation’ of global supply chains

Notes: The chart plots the share of maritime U.S. imports from China, Asia (excluding China), and the rest of the world (ROW), normalized at 100 in 2017:Q4. The data refer to shipments to all ports and customs containerized vessel value. Sources: Authors’ calculations using the U.S. Census Bureau.

While previous research in international trade has shown that tariffs are significantly changing global trade patterns (see Freund et al. 2023 and Gopinath et al. 2025 for product-level analyses), we know less about how individual firms manage this transition and even less about the role of financial intermediaries in enabling these costly adjustments.

In a new paper (Alfaro et al. 2025), we shed light on this critical question. We explore whether, and how, commercial banks helped US firms navigate supply chain disruptions after the 2018–2019 waves of tariffs imposed by the US on imported goods from China (henceforth, ‘China tariffs’).

Using newly linked data on US firms' trade activities and their banking relationships, we document the vital role of banks – especially that of banks with expertise in Asian trade finance – in helping firms find new suppliers and thus adjust to the new tariff regime more successfully.

Our analysis draws on two rich administrative datasets that provide a unique window into the micro-dynamics of supply chain relationships and financial intermediation. First, S&P Panjiva Supply Chain Intelligence, a shipment-level database that tracks US importers and their foreign suppliers, allows us to track firms' supplier relationships over time at a very granular level (product by product, supplier by supplier, country by country). Second, the Federal Reserve’s Y-14 dataset provides data on individual loan contracts between large US banks and corporate borrowers, many of which are manufacturing firms reliant on Chinese imports for their production. The trade-credit linked data enables us to analyse changes in firms' financing patterns – in particular, their demand for bank credit – in response to trade shocks, and how those changes vary with the business model of banks. The median firm in our data is private, dependent on bank credit, and eight times smaller than the median public firm in Compustat.

The challenge of changing suppliers

The 2018–2019 China tariffs were a significant shock to global supply chains. Companies that depended on Chinese suppliers for final or intermediate goods faced higher costs and had to decide whether to keep their partners, absorb the higher prices, or seek alternatives elsewhere. Many firms chose to reorient their sourcing strategies.

In our empirical analysis, we find that tariff-affected firms were significantly more likely to cut ties with Chinese suppliers and establish new trade relationships elsewhere in Asia and the rest of the world, extending the country-level findings in the literature (Handley et al. 2024) to the firm level.

But this shift was far from seamless. On average, firms took more than 2.5 years to establish new supplier relationships. We estimate that the search costs associated with switching suppliers amounted to around $1.9 million per firm, or roughly 5% of their annual sales revenue.

The critical role of banks

So, how did firms manage this complex and costly adjustment? Our study finds that commercial banks played a central role, not only by meeting importers’ demand for more credit, but also by offering valuable information about potential suppliers.

Using the trade-credit linked dataset, we show that tariff-hit importers sharply increased their demand for bank credit. Firms drew more heavily on their existing credit lines and took out new bank loans, often at higher interest rates, reflecting the financial strain of rebuilding supply chains.

Importantly, not all banks were equally helpful. Tariff-hit firms in a relationship with banks that specialise in financing trade with Asia performed significantly better. These firms secured cheaper credit compared to firms borrowing from other banks and were 15 percentage points more likely to find new suppliers outside China (Figure 2). They also re-established supplier relationships nearly three months faster and grew their Asian import shares by 5.6 percentage points more than comparable firms with non-specialized banks.

Figure 2 The value of specialised banks in supply chain realignment

Notes: The chart reports the increase in probability of entry (i.e. finding a new supplier) in Asia (excluding China) for tariff-hit importers with specialized banks compared to tariff-hit importers with other banks after the 2018-2019 China tariffs. See Table 9 in Alfaro et al. (2025) for details. Source: Authors’ calculations.

In short, having the right bank relationship significantly eased the burden of supply chain reallocation.

Why specialised banks matter

What gave specialized banks their edge? Two factors seem key: better financing terms and better information (Blickle et al. 2023, Paravisini et al. 2023).

First, firms borrowing from banks with trade finance expertise in Asian markets secured new loans at lower interest rates – close to 19 basis points cheaper – than firms working with other banks. Specialised banks offer lower-cost loans than other banks by leveraging knowledge of their trade-oriented borrowers’ creditworthiness and business opportunities in Asia. In turn, improved loan terms made it easier for firms to absorb the costs of searching for and onboarding new suppliers.

Second, specialised banks emerged as information hubs. They leveraged their informational advantage and local knowledge to assist clients in identifying new suppliers abroad. We show that US importers were more likely to match with new suppliers in those countries where their specialised bank also has a local office (branch/subsidiary), allowing it to pursue direct or syndicated lending to local borrowers, or has ties with correspondent banks. Moreover, after the China tariffs, specialised US banks’ fee income from advisory services increased significantly at their Asian subsidiaries compared to non-Asian subsidiaries, indicating that the Asian advisory and consulting business grew faster as they helped clients navigate the transition.

Interestingly, these benefits accrued to firms in a relationship with banks specialised in Asian trade finance. By contrast, relationships with banks specialising in European markets had no impact on firms' ability to diversify away from China to other Asian suppliers.

No signs of increased risk or substitution to trade credit

One natural concern is whether this surge in the demand for bank credit from firms affected by the China tariffs led to riskier lending practices. We find no evidence that specialised banks suffered from higher loan defaults or charge-offs during this period. Supporting firms' supply chain diversification did not come at the cost of weaker balance sheets.

We also find no evidence that firms replaced bank credit with increased trade credit from their Chinese suppliers – a reassuring sign that support from specialised banks was genuinely easing financial and informational bottlenecks rather than merely substituting one form of financing for another.

Conclusion

The global economy is increasingly vulnerable to trade shocks, geopolitical shifts, and other disruptions that rattle supply chains. Our findings highlight an underappreciated but vital part of supply chain resilience – the role of financial intermediaries.

Commercial banks can act as both financiers and information brokers, helping firms weather shocks and reconfigure their supply chains more swiftly and successfully. As policymakers and business leaders grapple with the challenges of building more resilient supply networks, recognising the importance of financial relationships – particularly that of banks’ specialised expertise in particular industries and geographies – is crucial.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the Federal Reserve System, or the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Aiyar, S, A F Presbitero, and M Ruta (2023), Geoeconomic Fragmentation: The Economic Risks from a Fractured World Economy, CEPR Press.

Alfaro, L, M Brussevich, C Minoiu, and A F.Presbitero (2025), “Bank Financing of Global Supply Chains”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 20164.

Alfaro, L and D Chor (2023), “Global Supply Chains: The Looming “Great Reallocation””, NBER Working Paper No. 31661.

Antràs, P, T Fort, and F Tintelnot (2017), “The margins of global sourcing: Theory and evidence from US firms,” American Economic Review 107(9): 2514–2564.

Antràs, P (2020), "De-globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age," CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15462.

Baldwin, R and R Freeman (2022), "Global Supply Chain Risk and Resilience," VoxEU.org, 6 April.

Blickle K, Z He, J Huang, C Parlatore, and A Saunders (2023), “Specialization in banking”, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Fajgelbaum, P, G Goldberg, P Kennedy, A Khandelwal, and D Taglioni (2024), "The U.S.-China Trade War and Global Reallocations," American Economic Review: Insights 6(2): 295–312.

Freund, C, A Mattoo, A Mulabdic, and M Ruta (2023), "US-China decoupling: Rhetoric and reality," VoxEU.org, 31 August.

Goldberg, P and T Reed (2023), “Is the Global Economy Deglobalizing? If So, Why? And What Is Next?,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 54: 347-423.

Gopinath, G, P-O Gourinchas, A F Presbitero, and P Topalova (2025), “Changing Global Linkages: A New Cold War?,” Journal of International Economics 153: 104042.

Grossman, G, E Helpman, and S Redding (2024), "When tariffs disrupt global supply chains,” American Economic Review 114(4): 988–1029.

Handley, K, F Kamal, and R Monarch (2024), “Rising import tariffs, falling export growth: When modern supply chains meet old-style protectionism,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 17(1): 208-238.

Paravisini, D, V Rappoport, and P Schnabl (2023), “Specialization in Bank Lending: Evidence from exporting firms,” Journal of Finance 78(4): 2049-2085.