The shifting trade landscape is a new major adverse shock for the EU economy

The year had started on a relatively positive note. Final data for 2024 showed EU GDP expanding by 1% — an overall modest pace, but a welcome shift after the stagnation of the previous year. Momentum kept steady in the first quarter, and with disinflation well on track, funding costs were set to decrease further. A tight labour market supported robust wage growth, expected to finally restore previous losses in real purchasing power. The absorption of Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funds was set to step up, while private sector balance sheets remained sound, offering a foundation for a much-needed surge in investment. With a newly agreed fiscal framework, consolidation was expected to proceed gradually, encourage reforms and preserve productivity enhancing expenditure, laying the ground for a broad, if modest, expansion.

The sweeping so-called “reciprocal tariffs” announced on 2 April sent shockwaves through the global economy. The near meltdown of the financial system in the days that followed the announcement prompted a suspension in their application (Baldwin and Barba Navaretti 2025), but the uncertainty unleashed by the erratic US policy swings is unlikely to subside in the near term (Figure 1). The partial rollback of the punitive bilateral tariffs that followed US-China escalation suggests that global trade relations may settle on a less protectionist stance than the current one, but risks remain. Even in the most positive scenario, a more fragmented global trade order is set to dominate the foreseeable future, while increased uncertainty is already weighing on sentiment.

Figure 1 Trade policy uncertainty and VIX index of financial volatility, EU

Like other economies, the EU is feeling the strain. The European Commission’s Spring Forecast (European Commission 2025a) significantly downgrades the EU outlook: real GDP growth is projected at just 1.1% this year, with only a modest acceleration to 1.5% in 2026.

Overall, by 2026, the volume of GDP would be 0.7 percentage points lower than in the Autumn Forecast. The negative gap with potential output is reopening and will not close over the forecast horizon. Crucially, excluding the post-pandemic rebound of 2022, the EU economy is set to operate below potential for nearly seven consecutive years, reinforcing the perception of an EU mired in low growth. That judgement, however, is misplaced. The sequence of global shocks in recent years – the pandemic, supply bottlenecks, energy price surges, geopolitical conflicts, and high inflation – has been without precedent. For structural reasons and due to its geographic exposure, Europe has been more severely affected than other advanced economies. The EU economy has demonstrated resilience, helped by timely and effective policy responses including at EU level.

Uncertainty and financial tightening weigh on trade and investment

Simulations with the European Commission’s QUEST model – based on the tariffs announced on 2 April – point to a rather modest drag on growth in the EU, mainly via the external channel (European Commission 2025b). Still, what happened on 2 April differs from a typical tariffs shock: it was accompanied by a sharp rise in trade uncertainty and a tightening of financial conditions. Trade policy uncertainty remains extremely elevated as the current situation remains unstable, and clarity over a potential new equilibrium is elusive. This is set to weigh on growth – even in the absence of further changes to the tariff rate.

Moreover, as argued in Benigno (2025), the magnitude, scope and abruptness of the tariff announcement forced investors to radically revise their outlook for corporate earnings, productivity and global growth. This activated a self-reinforcing cycle of asset price declines, margin calls and deleveraging, which exposed financial vulnerabilities. This is set to have a lasting effect, despite the partial recovery in financial markets that followed the suspension.

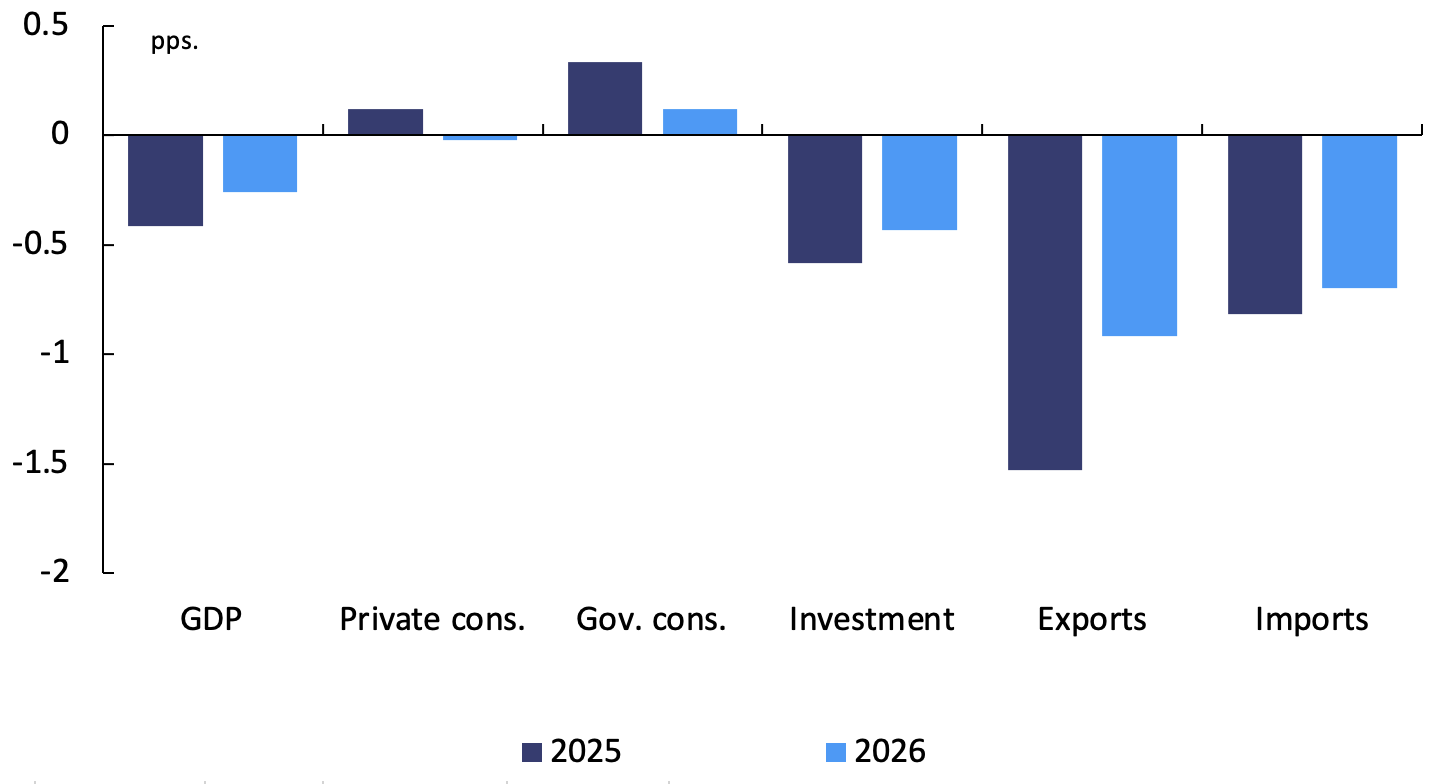

In the Spring Forecast, EU exports are now projected to grow by just 0.7% in 2025 and 2.1% in 2026 – some 2.5 percentage points (cumulatively) below the baseline of the Autumn Forecast (Figure 2). Trade in services – largely unaffected by tariffs – remains resilient, but exports of goods are set to contract in 2025 and register only a modest growth in 2026. With the risk of escalation looming, firms are reluctant to bear the high fixed costs of entering new markets – whether in the US or elsewhere.

Tighter financing conditions weigh both demand from partners and availability of export credit. Imports are also revised downwards, on account of the strong export-import link, partially offsetting the impact of downward revisions to exports.

Figure 2 GDP revision by component EU (Spring 2025 Forecast vs Autumn 2024 forecast)

Source: European Commission Autumn 2024 Forecast and Spring 2025 Forecast.

Capital expenditure is also heavily affected. After a nearly 2% contraction in 2024, investment is projected to recover only modestly: rising 1.5% in 2025 and 2.4% in 2026. Weaker exports reduce capacity utilisation, while uncertainty raises the value of waiting. On the financing side, banks had already tightened lending standards before April’s turmoil, and conditions are expected to tighten further as institutions reassess exposure to tariff risks.

Equipment investment is likely to be the most affected, recovering only gradually. In contrast, infrastructure remains resilient, largely supported by EU funding – especially under the RRF. Encouragingly, residential construction should turn the cycle after downsizing for almost two years. R&D spending is also expected to continue expanding, a sign that firms are still investing in future competitiveness (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Investment growth and contributions by asset, EU

Sources: European Commission Spring Forecast.

Consumption expands, but is held back by household caution

Despite subdued growth, the labour market remains strong. Employment rose again in 2024 and is expected to increase by another 1% over 2025–2026, implying 2 million new jobs. As job intensity normalises, the unemployment rate is forecast to fall to a historic low of 5.7% by 2026. Wage growth remains robust: nominal compensation per employee rose 5.3% in 2024 and will decelerate only gradually, ensuring a full recovery in real wages by end-2025.

Disinflationary forces gain momentum. Energy prices have fallen sharply in the aftermath of the tariff shock and are expected to remain subdued, with futures pointing downward. US-China trade reconfiguration is likely increasing competition in global industrial goods, exerting further price pressure in the EU – a pattern already observed during the 2017-2019 US-China trade war (Evenett and Espejo 2025). A stronger euro is also lowering import costs. These effects are only partly offset by persistent inflation in services and food. Euro area headline inflation is forecast to fall from 2.4% in 2024 to 1.7% in 2026. Core inflation is moderating more slowly.

Labour market strength and falling inflation support a moderate acceleration in consumption. Still, caution persists. Consumer sentiment weakened in March and April, reflecting consumers' gloom about the general economic situation and, more recently, concerns about their financial situation. The household saving rate remains elevated and is projected to decline only gradually over the forecast horizon. As a result, private consumption is expanding by 1.5% in 2025, with a marginal pickup in 2026 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Real consumption and saving, EU

Source: European Commission Spring Forecast.

Risks loom high and macroeconomic policy buffers are thin…

Risks to growth remain substantial. While the US pushed the pause button under market pressure, renewed trade escalation cannot be ruled out. That would not only depress trade further but also undermine domestic demand – tightening financial conditions and possibly reigniting inflation. Financial market vulnerabilities could resurface if sharp asset corrections occur, turning low growth into recession. Even under de-escalation, the global order is becoming more fragmented and volatile.

Markets expect further monetary easing, with policy rates likely to fall to the lower end of the ECB’s neutral range (1.75% to 2.25%) by 2026. Fiscal policy is also expected to return to a broadly neutral stance after a slightly contractionary 2024. Government deficits are set to hover around 3.3% of GDP. This suggests some modest scope for a more supportive policy stance – if the economic situation were to deteriorate beyond what is projected in the baseline. Yet this juncture calls for more than just cyclical stabilisation — it demands a renewed focus on the EU’s growth potential.

… highlighting the need to resolutely advance the growth agenda

The EU is not starting from scratch. Many proposals have already been tabled and renewed momentum could emerge in times of acute crisis.

Externally, the priority is to deepen trade partnerships and reduce risks from geographic and product concentration. The EU’s commitment to a rules-based global system and the reliability of its economic and regulatory framework are increasingly recognised as key assets. These can reinforce its role as a global trade hub and enhance its appeal to firms seeking predictable access to global markets. Moreover, at a time of greater financial fragmentation, renewed interest in euro-denominated assets – underpinned by a solid financial architecture and sound public finances – could lay the foundations for a greater international role for the euro (Cardani et al. 2025) and lower financing costs for governments and corporates alike.

Above all, the EU needs to reconnect savings with investment. This means pushing forward with the Saving and Investment Union, reducing market fragmentation, and ensuring that financial inflows are channelled into productive activities. But beyond funding, start-ups must also be confident they can scale up, tapping into a market of 450 million consumers. Deepening the Single Market – especially in services, digital, and energy – would unlock this potential, boosting productivity. So would recalibrating regulation to ensure that administrative burdens remain proportionate to intended benefits.

The world is becoming increasingly uncertain, more fragmented, and more volatile. But the EU still holds a strong hand. It’s time to play it well.

References

Baldwin, R and G Barba Navaretti (2025), “US misuse of tariff reciprocity and what the world should do about it”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Benigno, G (2025), “Why the tariffs caused turmoil in financial markets”, VoxEU.org, 11 Apr 2025

Caldara, D, M Iacoviello, P Molligo, A Prestipino and A Raffo (2020), “The economic effects of trade policy uncertainty”, Journal of Monetary Economics 109: 38-59

Cardani, R, M Kühl, J Peppel-Srebrny and R Strauch (2025), “Exchange rate uncertainty, tariff hikes, and adjustment costs”, VoxEU.org, 12 May 2025.

European Commission (2025a), “Spring 2025 Economic Forecast: Moderate Growth Amid Global Trade Uncertainty”, Institutional Paper 318, 19 May.

European Commission (2025b), “The Macroeconomic Effect of US Tariff Hikes”, Special Topic.

Evenett, S and F M Espejo (2025), “Redirecting Chinese Exports from the USA: Evidence on Trade Deflection from the First U.S.-China Trade War”, Zeitgeist Series Briefing 62, Global Trade Alert, 14 April.

Osnago, A, R Piermartini and N Rocha (2025), “Trade policy uncertainty as barrier to trade”, WTO Working Paper ERSD-2015-05.